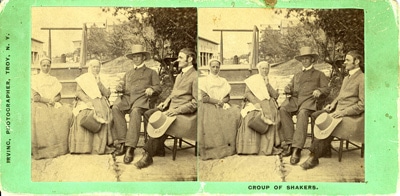

Effective communal groups, including the Shaker community at Hancock, find ways to balance the internal dynamic of differentiation and equality among members. No matter how small the distance, there is still a distinction between leader and member; the few and the many. The Shakers were able to largely resolve the distinction between Ministry and “rank and file” Believers in favor of communal equity and the success of the group as a whole. Writings by some apostates include observations about this dilemma, one that was typically settled by the independent voice taking leave of the community.

Shaker community organization has always been centered in tenets of faith and Hancock’s early days featured women as eldresses alongside men in the role of elders. Joseph Meacham of Mount Lebanon, NY is credited with establishing the dual leadership structure that Lucy Wright’s tenure regularized for the societies as a whole. After 1784, Mount Lebanon was the seat of the Central Shaker Ministry, and their decisions were passed down to the rest of the Shaker communities who were expected to follow their lead.

Shaker community organization has always been centered in tenets of faith and Hancock’s early days featured women as eldresses alongside men in the role of elders. Joseph Meacham of Mount Lebanon, NY is credited with establishing the dual leadership structure that Lucy Wright’s tenure regularized for the societies as a whole. After 1784, Mount Lebanon was the seat of the Central Shaker Ministry, and their decisions were passed down to the rest of the Shaker communities who were expected to follow their lead.

Often this distinction between leader and member is expressed in the material surroundings of daily life. Certain rooms and buildings at Hancock speak to this complementarity or dynamic.

Dining Rooms

In each Shaker community, male elders and female eldresses met to provide religious and social guidance for the group as a whole. The spaces they used and which were constructed for them were not quite the same as spaces for work or accommodation (e.g., sleeping quarters) provided for members. In the Brick Dwelling at Hancock, the second floor dining areas are efficient places for providing physical nourishment and also depict the equity and differentiation between religious leaders and membership. The Ministry Dining Room is located beside, but separate from, the large communal dining room used by the members. The Ministry also had a separate entrance in their dining room so that they had no need to file in with the rest of the Believers.

- Main Dining Room

- Private Entrance to Dining Room

- Ministry Dining Room

Ministry Shop

Shaker religious beliefs emphasized union, which required religious leaders to work as every member was expected to work but with the additional responsibility of supervising ideas and practices pertaining to faith. Thus work space for elders and eldresses, often called the Ministry Shop, was designed to be closer to the meeting house and members might visit them to discuss ordinary community concerns. However, this location also allowed elders to look across the road at the rest of the village and keep an eye on the activities unfolding among the members. This social yardstick of close but not too close created the material context for group cohesion and communal success.

Elders and eldresses were often the community’s primary basket makers, and the Ministry Shop at Hancock recreates a workroom that would have been used by the leaders of the village.

- Ministry Shop

- Ministry Workshop

- Ministry Workshop

- Ministry Baskets

Meeting House

Visiting Ministry members from other communities were given lodging that was separate from the large dwelling houses, and separate from the resident Ministry’s rooms. The visitors were provided with bedrooms and a dining space upstairs in the Meeting House.

- Meeting House Bedroom

- Meeting House Bedroom

Hired Men’s Shop

The Hired Men’s Shop speaks to differentiation by extension to outsiders. The hired men were not Shakers yet their labor was crucial to the community’s economic standing: the thorny question of where to lodge them was ultimately settled by keeping their quarters close to the Trustees’ House and the ‘public’ face of Hancock. The Believers provided good lodging for the Hired Men, but at arm’s length from the core of the Hancock community.

- Worldly Possessions

- Hired Mens

- Worldly Possessions