This online exhibition is presented in conjunction with Pittsfield 250, a year-long celebration of the 250th anniversary of Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, more commonly called the Shakers, established a village in West Pittsfield around 1790. It was the third village founded by the Shakers in America.

Most of the central or “Church” Family (the current museum campus) is located in the town of Hancock, but there were also several outlying “families” or groups of Shakers that lived within the city limits of Pittsfield. The East Family lined both sides of Route 20 from Lebanon Avenue past Cloverdale Road, including the railroad tracks. The Second Family, also on Route 20, was located between the East and Church Families. Some buildings, the last remnants of these families, can still be seen along Route 20, together with the marble gate posts that are of a telling Shaker design.

Although most of the Church Family sits in the town of Hancock, the Trustees’ Office and Store is located just across the town line in Pittsfield. This building is the place where the Shakers showed their “public face” and conducted their business transactions with people from “The World”, the Shakers’ term for non-believers. The thoughtful placement of their office and store in Pittsfield set up a mutual relationship with the town and its residents that continues into the present day.

While one of the Shakers’ goals was to live apart from “The World” in a communal society and create a heaven on earth, they also recognized the fact that they needed the outside world for legal support, as a customer base, and to recruit converts. They paid taxes to the city of Pittsfield, perhaps because they thought it their duty to support the town that allowed them to live and worship in peace.

Recognizing the Shakers

The first written mention of the Shakers appears in the Pittsfield Town Meeting Records as early as 1781. In a meeting held on March 12, 1781, items numbered 22 and 23 on the agenda were passed. They state: “That a Committee be chosen to consult and devise some proper Measures to take with those people known by the Name of Shakers.”

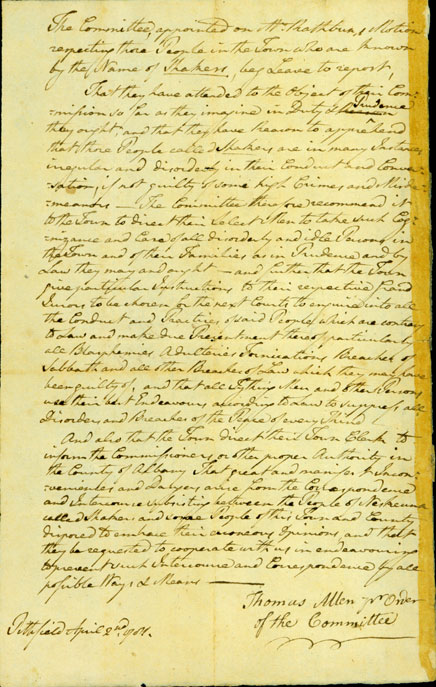

The Committee appointed on Mr. Rathbun’s Motion respecting those People in the Town who are known by the Name of Shakers, beg Leave to report,

That they have attended to the Object of their Commission so far as they imagined in Duty & Prudence they ought, and that they have Reason to apprehend that those People called Shakers are in many Instances irregular and disorderly in their Conduct and Conversation, if not guilty of some high Crimes and Misdemeanors – The Committee therefore recommend it to the Town to direct their Select Men to take such Cognizance and Care of all disorderly and idle Persons in the Town and of their Families as in Prudence and by Law they may and ought – and further that the Town give particular Instructions to their respective Grand Jurors to be chosen for the next Courts to enquire into all the Conduct and Practices of said People which are contrary to Law and make due Presentment thereof particularly all Blasphemies Adulteries Fornications Breaches of Sabbath and all other Breaches of Law which they may have been guilty of, and that all Tything Men and other Persons use their best Endeavour according to Law to suppress all Disorder and Breaches of the Peace of every Kind.

And also that the Town direct their Town Clerk to inform the Commissioners or other proper Authority in the County of Albany That great and manifest Inconveniences and dangers arise from the Correspondence and Intercourse existing between the People of Niskeuna called Shakers and some People of this Town and County disposed to embrace their erroneous Opinions and that they be requested to cooperate with us in endeavoring to present such Intercourse and Correspondence by all possible Ways & Means –

Thomas Allen per Order of the Committee

Pittsfield April 2nd, 1781

Image courtesy of Berkshire Athenaeum.

The Committee submits its report at the next month’s meeting, held on April 2, 1781. The Congregational Minister of Pittsfield, the Reverend Thomas Allen, presents the findings on behalf of the Committee, which was made up of “five Gentlemen.”

Public opinion of the Shakers begins to change as the nineteenth century is ushered in. Their clean, efficient villages and affordable, reliable products make the Shakers the recipients of a well-deserved mention by the Reverend Thomas Allen in his 1808 pamphlet A Historical Sketch of the County of Berkshire. He states that the Shakers are “very harmless, innocent people, good citizens, and honest, industrious, peaceable members of society. They are good farmers and artists, and offer nothing for sale that is deceptive.” This change of heart by Reverend Allen is a testament to the perseverance of the Shakers, even in the face of initial adversity from the surrounding community.

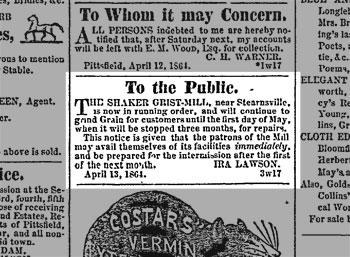

Shakers In The News

During the nineteenth century, the local papers often reported on happenings at the Shaker village, especially if they were particularly interesting stories for people of “The World.” The Pittsfield Sun, published from 1800 to 1906, was just one among many Berkshire County newspapers. “The Eagle” as it is referred to by locals, started its life as a joining of the Argus and the Berkshire Journal in 1831, became the Massachusetts Eagle in 1834 and finally known as the Berkshire County Eagle in 1853.

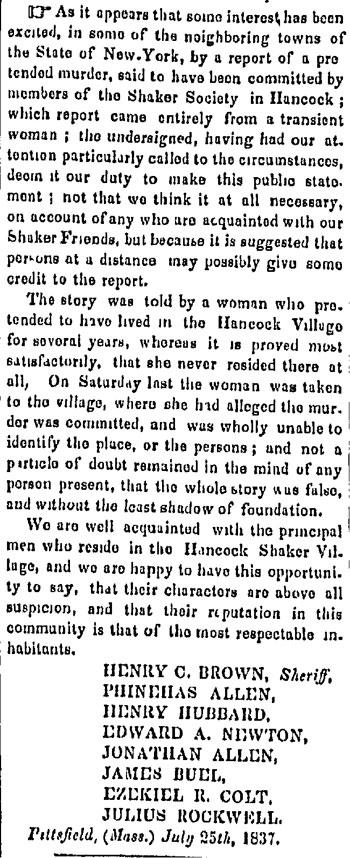

In 1837 a “transient woman” accused the Hancock Shakers of murder. The article makes it clear that the Berkshire County Sheriff, Henry C. Brown, was called upon to clear up the matter. The last paragraph of the article is an exoneration of the Shakers and reinforces their good standing within the community.

Courtesy of Berkshire Athenaeum.

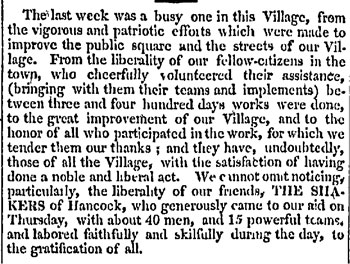

The Pittsfield Sun mentioned the Shakers when they donated their time and resources outside the boundaries of their village, in order to improve the town square and streets in Pittsfield in 1824.

Courtesy of Berkshire Athenaeum.

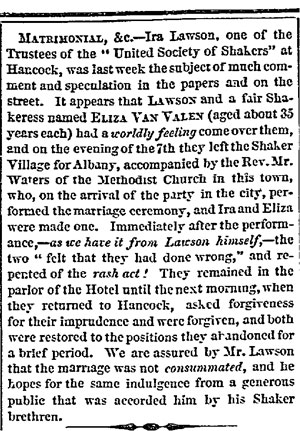

In a story that would certainly make tabloid headlines today, a Shaker Trustee and a “fair Shakeress” ran away from Hancock to get married in June of 1871. While this in itself might not seem to be newsworthy, the Shakers were (and are) a celibate society who did not marry, which allowed Believers to focus more fully on the spiritual goal of salvation. Nevertheless, the two were married in Albany, and the ceremony was presided over by the Reverend Mr. Waters, of the First Methodist Church in Pittsfield.

Courtesy of Berkshire Athenaeum.

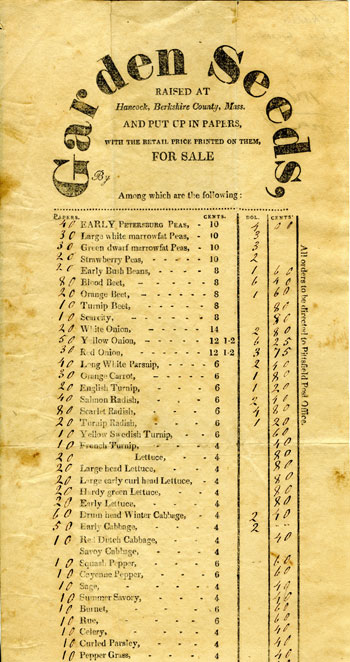

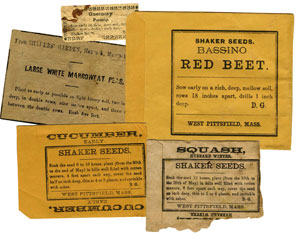

Shakers as Entrepreneurs

The Shakers were smart businessmen and women, who appointed members from their society as “Trustees,” or those who were entrusted with dealing with the business of “The World.” They were the public face of the community and were always known as upstanding citizens who were honest in their dealings and sold reliable products.

Image courtesy of Berkshire Athenaeum.

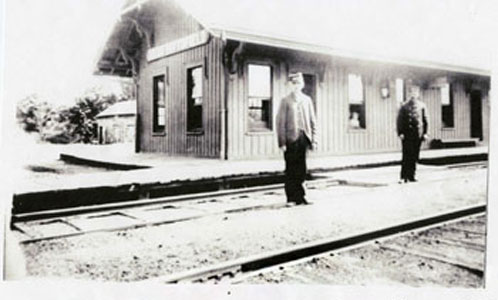

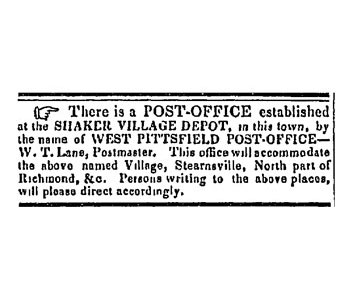

The use of the Pittsfield Post Office was a necessity for the Shakers, even though it brought them into greater contact with the world outside their enclaves. The postal system was important as it allowed the Shakers to correspond regularly with other Shaker communities and to increase the radius where they could sell their goods.

In August of 1854, East Family Elder Augustus W. Williams became postmaster of the West Pittsfield Post Office, one of the few Shakers to hold a position in “The World.” He remained postmaster until 1888, and while he mainly handled the Shakers’ own mail, he also certainly handled the mail of their Pittsfield neighbors. By 1890, the name of the station was changed to West Pittsfield, and closed in the 1930s. The building was torn down in the early 1940s, but the site can still be found on what is currently Cloverdale Road.

Shaker Farmers

The sixty-sixth annual exhibition of the Berkshire Agricultural Society was held at Pittsfield, the 5th, 6th, and 7th of October [1875]. Of grade animals there were 99 entries; viz., Fat cattle, 5; working oxen, 15; steers, 7; dairies, 5; milch cows, 21; breeding cows, 11; heifers, 18; calves, 7; herds, 10; – aggregating 147 entries of neat-stock, and numbering 256 animals. Noticeable among these was the Dutch cow, belonging to the West Pittsfield Shakers, which is milked three times a day. Owing to her great productiveness, $1,200 has already been refused for her.

(p. xxx, excerpted from Charles L. Flint, Twenty-Third Annual Report of the Secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Agriculture: 1875, Boston: Wright & Potter, State Printers, 1876)

Shaker Snapshots

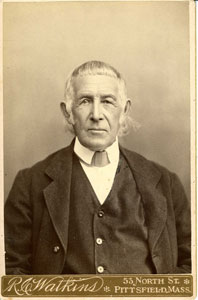

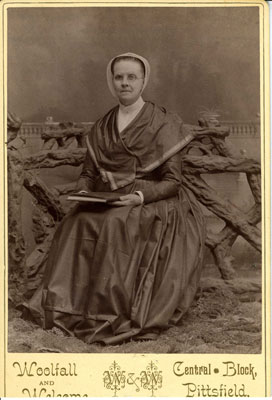

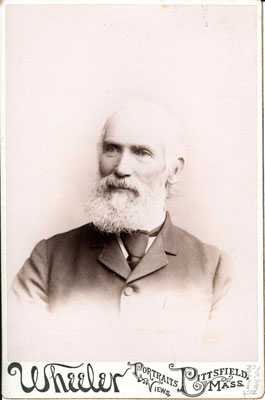

Throughout the nineteenth century, the Shakers patronized several local Pittsfield photographers. They journeyed to North Street and sat for their portraits, the only thing distinguishing them from worldly customers was their mode of dress. Shakers embraced the relatively new medium of photography just as they embraced most new technological advances throughout their history. They used their portraits as a means of community documentation, often commemorating appointments of elders and trustees. The Shakers were meticulous record keepers of every aspect of community life as is evidenced through their journals, account books and ledgers. They also shared their images with brothers and sisters in distant Shaker communities by way of introduction. The Shakers’ interactions on North Street and the portraits that resulted from these visits put forward a public face that made them seem more accessible and “real” to the outside world.

Ripening Angels

In the nineteenth century some Shaker communities sent promising young brothers to medical school so that they could return and care for their ailing brethren and sisters. In the early twentieth century, however, there were no doctors living in the Hancock community. A visiting nurse would make rounds if called upon, but the Shakers were often treated for more serious illnesses at local hospitals.

Elder Louis Basting was admitted to the House of Mercy Hospital in Pittsfield (which became Berkshire Medical Center in later years) in March of 1905 with “a complication of diseases.” Sadly, he passed away in August of the same year.

Pictured here is a Shaker burial shroud. Shaker funerals were certainly somber affairs without much pomp and circumstance. Their funerals functioned as a way to recognize the end of one’s earthly existence, but more importantly, to celebrate the Shaker soul and its entrance into heaven. Once there, they would be embraced by Mother Ann Lee and live on with their brethren and sisters who went before them to that holy place. Funerals in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were arranged with the help of Wellington and Crosier on East Street in Pittsfield, which opened in 1893. Currently it is Wellington Funeral Service, and is still located on East Street.

Pictured here is a Shaker burial shroud. Shaker funerals were certainly somber affairs without much pomp and circumstance. Their funerals functioned as a way to recognize the end of one’s earthly existence, but more importantly, to celebrate the Shaker soul and its entrance into heaven. Once there, they would be embraced by Mother Ann Lee and live on with their brethren and sisters who went before them to that holy place. Funerals in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were arranged with the help of Wellington and Crosier on East Street in Pittsfield, which opened in 1893. Currently it is Wellington Funeral Service, and is still located on East Street.

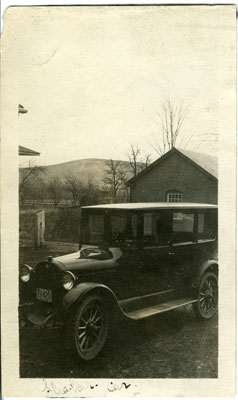

Shakers and the Automobile

The Brewer Bros. salesroom, garage and service station opened in 1916, and was originally located at 141 West Street. In 1925, the dealership moved to 192-196 South Street. The Pittsfield location closed in 1966.

Shakers and Community Celebrations

In late 1892, the Shakers were asked to participate in a parade to celebrate “the discovery of this great and beautiful land,” most likely referring to the Columbus Day holiday. Sister Emoretta Belden wrote the following excerpt for the “Notes About Home” section in the the Shakers’ monthly publication, The Manifesto.

Nov. 5, 1892 The discovery of this great and beautiful land was honored by our scholars with appropriate exercises. Our neighboring city, Pittsfield, carried to a successful close quite an interesting programme. About thirty business men had floats in the Grand Parade of the day to exhibit their varied kinds of goods. At the solicitation of the Committee of Arrangements Br. Ira [Lawson] permitted his millers to turn out our mill team and take part with the others. By placing boards across the top of the carriage, a platform was made on which to set a huge mill-stone, the “sign of the honest miller.” Barrels of flour and bags of corn were open to show their contents, while polished scales and shovels, added to the beauty of the float. Bunting and flags were profusely used in the decorations. The carriage was drawn by six large horses, and presented a very fine appearance. Others evidently agreed with us, as it was assigned a place at the head of the long line of floats.

This image depicts a Fourth of July parade at Park Square in 1911. The Shakers’ float can be seen in the foreground with a brother leading the team of horses and sisters sitting around a table on the carriage. The irony of this image lies in the fact that at this time there were certainly not enough Shaker brethren living at Hancock to make up the numbers seen in this photo. Therefore, these are probably not Shakers, but merely people in Shaker dress. It is likely that they received permission to create this float from the Shakers still residing at Hancock. The Shakers were proud of their history with the city of Pittsfield, and were willing to be recognized as such.

This image depicts a Fourth of July parade at Park Square in 1911. The Shakers’ float can be seen in the foreground with a brother leading the team of horses and sisters sitting around a table on the carriage. The irony of this image lies in the fact that at this time there were certainly not enough Shaker brethren living at Hancock to make up the numbers seen in this photo. Therefore, these are probably not Shakers, but merely people in Shaker dress. It is likely that they received permission to create this float from the Shakers still residing at Hancock. The Shakers were proud of their history with the city of Pittsfield, and were willing to be recognized as such.

Photograph by Edwin Hale Lincoln, Courtesy of Berkshire Athenaeum

Shaker Schooling

Shaker children received an excellent education in the early nineteenth century. The boys went to school during the winter, leaving the rest of the year open for farm chores, and the girls went to school during the summer months. The schoolhouse was built at the Church Family in the 1820s, and was soon recognized as a separate school district by the town of Hancock. It became a public school that was open to local children from the surrounding communities as well as Believers. A second public school was established in West Pittsfield, most likely overseen by the East and Second Families of Shakers.

In 1900, Martha Corson was a young girl being raised by the Shakers and being educated at the Church Family’s school. She recalled how the Hancock school district was reviewed each year by a school committee, which was then replaced by a superintendent who made his rounds from Pittsfield by bicycle.

Acknowledgments

A great deal of thanks is owed to Christian Goodwillie, former Curator of Collections, who provided me with the information to start this project.

Many thanks to my colleagues Todd Burdick and Laura Wolf for their editing and content suggestions.

The web design wizard of Hancock Shaker Village: Nicole Desjardins … if you can dream it, she can design it.

Rob Kestyn of Brilliant Graphics

The Berkshire Athenaeum Staff in the Local History Department: Ann-Marie Harris, Kathleen Reilly and Liz Lockyer

Thanks to Peter Hansen, Mary Rentz, Christy Cordova, Magda Gabor-Hotchkiss, and Glendyne Wergland.