The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, more commonly known as the Shakers, are a religious group founded on the principles of celibacy, communal living, confession of sin, and most importantly, equality. The Shakers believed that all were equal in the eyes of God, and allowed anyone to join their communities, provided that they turned over their property and all material wealth once they committed to communal life. This placed all Believers on the same plane, where property was owned by the collective group, and food and necessities were provided to all, as long as you lived a devoted, spiritual life. This idea of equality extended to all races and sexes, and the Shakers welcomed many African Americans into their communities from their eighteenth century beginnings.

U.S Congressman William Loughton Smith was traveling in New York with President George Washington on August 29, 1790. The official party took in the healing waters of Lebanon Springs and from there followed a popular tourist route to observe the nearby Shaker meeting at New Lebanon.

In a long, low room of a very neat building painted white, were about fifty men and from eighty to one hundred women; arranged in rows, [who] sung or rather howled sundry strange tunes (one of them was “The Black Joke”), to which the men and women danced in uniform step, occasionally all turning around…There were two negroes among the dancers, one of them was the best dancer there; all ages joined in the dance.

-Excerpt from Albert Matthews, ed., Journal of William Loughton Smith, 1790-1791, Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

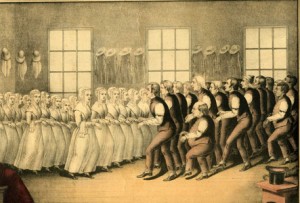

A popular print produced around 1830 depicted Shakers dancing at Mt. Lebanon, New York, where the viewer can pick out two faces that seem to stand out in the back row of the brethrens’ lines. They are clearly dressed in the same clothing and are performing the same dance steps as the men in the front lines. However, the difference is that these men are African Americans. There are several documented names of black Shakers during the early years of the Mt. Lebanon community, and the men depicted in the print have been identified as Ransom Smith (1795-1876) and Nelson Banks (1800-1878) by Shaker scholar Steve Paterwic.

A popular print produced around 1830 depicted Shakers dancing at Mt. Lebanon, New York, where the viewer can pick out two faces that seem to stand out in the back row of the brethrens’ lines. They are clearly dressed in the same clothing and are performing the same dance steps as the men in the front lines. However, the difference is that these men are African Americans. There are several documented names of black Shakers during the early years of the Mt. Lebanon community, and the men depicted in the print have been identified as Ransom Smith (1795-1876) and Nelson Banks (1800-1878) by Shaker scholar Steve Paterwic.

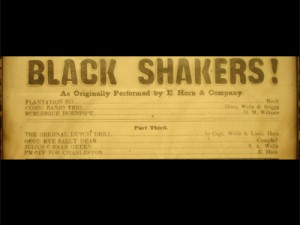

An 1851 broadside from the Chestnut Street Theater in Philadelphia advertises an act called Black Shakers! While there were certainly black Shakers living as Believers throughout the Shaker world at this time, the performers on stage in Philadelphia were not black, nor were they Shakers. The broadside was promoting a popular nineteenth century American amusement – the minstrel show. Scholar Rob Emlen has shed light on the fact that these were white actors in blackface makeup. They were parodying Shaker worship as well as the struggle of African Americans to gain greater standing in a predominantly white society. These troupes had little knowledge of actual Shaker life or music, and the fact that African Americans were accepted as full members of Shaker society may have surprised the traveling minstrel performers.

An 1851 broadside from the Chestnut Street Theater in Philadelphia advertises an act called Black Shakers! While there were certainly black Shakers living as Believers throughout the Shaker world at this time, the performers on stage in Philadelphia were not black, nor were they Shakers. The broadside was promoting a popular nineteenth century American amusement – the minstrel show. Scholar Rob Emlen has shed light on the fact that these were white actors in blackface makeup. They were parodying Shaker worship as well as the struggle of African Americans to gain greater standing in a predominantly white society. These troupes had little knowledge of actual Shaker life or music, and the fact that African Americans were accepted as full members of Shaker society may have surprised the traveling minstrel performers.

The Shakers welcomed all races into their society, and when one of their own was in danger, they took measures to prevent their departure. Believers would often purchase the freedom of slaves in the southern communities.

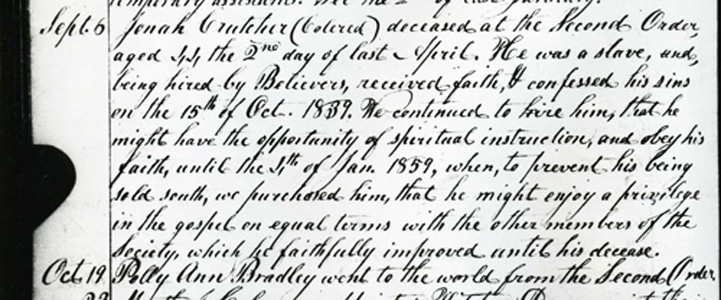

Jonah Crutcher (Coloured) deceased at the W.F. [West Family], of dyspepsia, being 44 years old the 2nd day of last April. He was a slave, and being hired by Believers, received faith in their testimony and confessed his sins on the 15 of October, 1839. As he continued to be a faithful Believer we continued to hire him, that he might have an opportunity of receiving spiritual instruction and obey his faith, till the 4th of January 1859, when it was apparent that he would be sold South and we purchased him that he might enjoy a privilege in the gospel on equal terms with the rest of us, which he did and continued faithful until the day of his decease. He was much respected and beloved in the family where he resided, which was not misplaced for he was worthy.

-Journal of 1843, Pleasant Hill, Kentucky

Excerpt from Church Records, Book A, Pleasant Hill, Kentucky, 1845. Image courtesy of the Harrodsburg Historical Society, Kentucky

Henry Jackson

Born in Washington in 1827, Jackson’s mother was a free woman and his father was a slave. He was sold into slavery at the age of three months. He escaped at age 18 with the help of a man from Albany, traveled there and then went on to Canaan, New York. He lived at a farm in that town where the kind owner cared for the “young fugitive” and taught him the blacksmithing trade as well as teaching him to read and write. In 1859 he married a woman named Duesey (or Densey) and “removed to Stearnsville in this town, near the Hancock Shakers, whom, he says, he found such excellent people to live with, that he has remained with them ever since. Joseph Patten, the first Trustee of the Church family, rendered him especial assistance in establishing himself in business in the shop where he has since won a high character as a workman, and also the esteem of all who came in contact with him.” Though Jackson never became a Shaker, he respected the Believers who helped him set up his shop with the East Family of the Hancock community.

Jackson went on to answer the call of the U.S. government, and accepted a commission to recruit soldiers for the now-famous African American Massachusetts 54th Regiment.

Interestingly, there was an African American woman named Helena Jackson who was listed in the 1850 U.S. Census as residing at the West Pittsfield (or Hancock) Shakers. She was aged 40 in 1850, and though too old to be the wife of Henry Jackson, Scholar David Levinson suggests that she could have been his mother.

Evidence of African American Believers at Hancock is sparse, unlike at other Shaker communities such as Watervliet, New York, the villages in Ohio and Pleasant Hill and South Union, Kentucky. Nevertheless, the Shakers at Hancock (often referred to as West Pittsfield in town records) had several African American neighbors and hired help who lived nearby. The Foster, Hamilton and Fillimore families are all listed as residing in dwellings “down the road” from the West Pittsfield Shakers in the 1850 U.S. Census.

Phoebe Lane

-adapted from Elizabeth Shaver in The Shaker Image (Hancock Shaker Village, Pittsfield, MA 1994)

Harriet Jones

Harriet Jones, an African American sister in Philadelphia and Watervliet, New York, was witnessed having a vision in September of 1919. In a letter from Sister [Minnie] Catherine Allen to her friend Rosalie Smith (of Williamstown, Massachusetts) she writes:

Hav[e]ing returned from the North Sat. P.M., while at the evening meal the colored Sister, Harriet Jones said “Standing by your side and bestowing love and blessing upon you I see Eldress Polly Lee and another whose name is given as Cynthia Dryer. Do not know the connection, have never seen nor heard of the latter but am sensible of a strong attachment between the two and they are both thanking you for your efforts on behalf of those so dear to them in the family where they had labored + loved when in earth life.

The Shakers’ idea of equality extended to all in the community, so that any member, black or white, was capable of communicating with the spirit world. Harriet Jones had certainly witnessed the visions of Eldress Rebecca Jackson in Philadelphia, so the practice was already familiar to her when she came to Watervliet in 1883.

Visions and “gifts” from the spirit world were common during the “Era of Manifestations” or “Mother’s Work” (late 1830s to early 1860s) so although it was uncommon for a Shaker to communicate a vision in the twentieth century, it was not unheard of. However, throughout Shaker history it was a common occurrence for Believers to have visions of their forebears. The barrier between the spiritual and temporal worlds was permeable for the Shakers, and there was frequent communication between the realms.

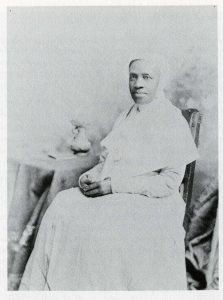

Rebecca Jackson

Rebecca Jackson (1795-1871) was a free African American woman who was born and lived much of her life in Philadelphia. She was married and she and her husband lived in her brother’s household, while he made a name for himself as a preacher and elder in the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Jackson worked as a seamstress, and cared for her widowed brother’s children, as she had none of her own. She had a religious awakening or conversion experience in July of 1830, during a thunderstorm. She began taking direction from her “inner voice,” which led her to several preaching tours, and finally to two different religious separatist groups in New York.

In 1840, she was associated with a group of Perfectionists, founded by Allen Pierce, and lived with them in Albany. In 1843, however, a schism took place within the group, seemingly over the question of celibacy, as the Perfectionists believed in “complex marriage.” Jackson, who had been celibate since her conversion experience, led a group of Perfectionists to join the Shakers at Watervliet, where she finally found the spiritual family she had been searching for.

Jackson lived at the South Family of Watervliet for four years, from 1847 to 1851. She was attracted to the ideas of equality that existed within Shakerism, both for women and for African Americans. The Shakers recognized Jackson as a true “prophet” and she freely preached in Sabbath meetings. Jackson, however, could not submit fully to her Shaker elders, as she was called by her inner voice and felt she had to follow wherever it led her. Her inner voice led Jackson back to Philadelphia in order to help “her people” or potential black converts there. This first trip back to her home city and the establishment of a Shaker society there was not sanctioned by the ministry in the north, and Jackson felt ill at ease about the venture for the entire six years she remained there. She returned to Watervliet in 1857 and gained the blessing of Eldress Paulina Bates after she was given permission by her inner voice to be obedient to Shaker authority. Jackson journeyed back to Philadelphia in 1858, and held her first official meeting as a Shaker eldress in 1859. The ministry at Watervliet and Mt. Lebanon took an active interest in the fledgling society in Philadelphia and made frequent trips there, even during the years when the group was not officially recognized, as well as after Jackson’s death.

There are few extant writings by Jackson’s hand after 1858, until her death in 1871. She was certainly still having visions and revelations, and leading her small, mostly African American Shaker family as a new type of Eldress. The society continued to thrive under Jackson’s protégé, Rebecca Perot (who took the name “Mother Rebecca Jackson” after Jackson’s death) for another forty years.

Thanks to: Tina Agren at Sabbathday Lake Shaker Museum, Todd Burdick, Laurie Whitehill Chong at Fleet Library at the Rhode Island School of Design, Rob Emlen, Nicole Marie Desjardins, Larrie Curry and Susan Hughes at the Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill, David Levinson, Magda Gabor-Hotchkiss, Christian Goodwillie, Tommy Hines, Steve Paterwic, Jerry Sampson at the Harrodsburg Historical Society, Glendyne Wergland, Laura Wolf, and Ilyon Woo.

Church Records, Book A, Pleasant Hill, Kentucky, 1845. HSV photocopy #6449 a & b.

Emlen, Robert P. “Black Shaker Minstrels and the Comic Performance of Shaker Worship,” American Communal Societies Quarterly, Vol. 4, no. 4 (October 2010): 191-217.

Humez, Jean McMahon, ed. Gifts of Power: The Writings of Rebecca Jackson, Black Visionary, Shaker Eldress. (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1981).

Journal of 1843, Pleasant Hill, Kentucky.

Letter from Sister Catherine (Minnie) Allen of Watervliet, N.Y. to Rosalie Smith, September 28, 1919, HSV #1617.

Albert Matthews, ed., “Journal of William Loughton Smith, 1790-1791,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society.